Hi everyone! Thanks so much for tuning into the latest post of Saving the Shtetlach, my online blog detailing my travels through Central and Eastern Europe discussing Jewish life and culture. It has been three weeks since I last wrote and I am sorry for the delay in my writing. I really appreciate your taking the time to read this now.

There are several reasons for my not posting over these past few weeks. I’m now working full time at the Jewish Museum of Maryland and while the job has been wonderful, when I come home I am exhausted and it’s been hard to write anything good. In addition, my growing concern with what’s been going on between Israel and Gaza has caused me a fair amount of writer’s block.

I am going to talk about two people that I learned about on this past trip I took to Poland. Their heroic stories set an example for all of us because they show that heroism does not rely on one’s race, ethnicity, nationality or religion. When it comes to it, heroism requires courage, morals, and a willingness to take risks for what you believe in. I’m going to tell you about two people who had all of these things and used them to save lives.

There are several reasons for my not posting over these past few weeks. I’m now working full time at the Jewish Museum of Maryland and while the job has been wonderful, when I come home I am exhausted and it’s been hard to write anything good. In addition, my growing concern with what’s been going on between Israel and Gaza has caused me a fair amount of writer’s block.

I am going to talk about two people that I learned about on this past trip I took to Poland. Their heroic stories set an example for all of us because they show that heroism does not rely on one’s race, ethnicity, nationality or religion. When it comes to it, heroism requires courage, morals, and a willingness to take risks for what you believe in. I’m going to tell you about two people who had all of these things and used them to save lives.

The first person I will discuss is a man I learned about by visiting a museum dedicated to him in Krakow. He is a very famous man and you have probably heard of him. He was a factory owner in Poland who saved over 1,200 Jewish lives during the Second World War. A very famous movie was made about him by director Steven Spielberg. Some of you may have seen the movie Schindler’s List, and in this post I am going to tell you about the man, the hero, Oskar Schindler.

In the latter part of this post, I’m going to tell you about a woman whose story I learned by hearing her tell it herself during my time spent at the Galicia Museum in Krakow. While she saved the life of one Jew, rather than a 1,200, her story is just as poignant and it is just as important to be told and remembered. This woman’s name is Mirosława Gruszczyńska and with her sister and mother, she hid a Jewish girl from the Nazis during the Second World War. With her family, she saved a young life, enabling this victim to survive the war and make a new life for herself and her future family.

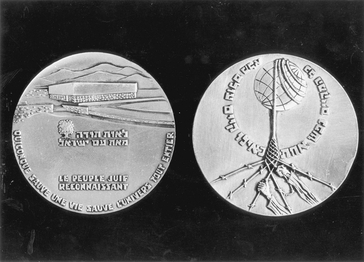

Both of these people have been named Righteous Among the Nations, a special award presented by the state of Israel to non-Jewish people who saved Jews during the Holocaust. Each person who has been named a Righteous Gentile has an unbelievable story. I am very excited to share the stories of two of them with you.

Oskar Schindler, who was born in 1908 to an ethnic German-Sudeten family in Austria-Hungary, did not intend that his life would be remembered as one of a hero – a man who saved more than 1,200 Jews. He was a man who tried his hand at many different business ventures and often failed.

In the latter part of this post, I’m going to tell you about a woman whose story I learned by hearing her tell it herself during my time spent at the Galicia Museum in Krakow. While she saved the life of one Jew, rather than a 1,200, her story is just as poignant and it is just as important to be told and remembered. This woman’s name is Mirosława Gruszczyńska and with her sister and mother, she hid a Jewish girl from the Nazis during the Second World War. With her family, she saved a young life, enabling this victim to survive the war and make a new life for herself and her future family.

Both of these people have been named Righteous Among the Nations, a special award presented by the state of Israel to non-Jewish people who saved Jews during the Holocaust. Each person who has been named a Righteous Gentile has an unbelievable story. I am very excited to share the stories of two of them with you.

Oskar Schindler, who was born in 1908 to an ethnic German-Sudeten family in Austria-Hungary, did not intend that his life would be remembered as one of a hero – a man who saved more than 1,200 Jews. He was a man who tried his hand at many different business ventures and often failed.

When the Second World War began, Schindler began a factory in Krakow, Poland. The factory was called the Deutsche Emaillewaren-Fabrik (German Enamelware Factory), nicknamed “Emalia.”

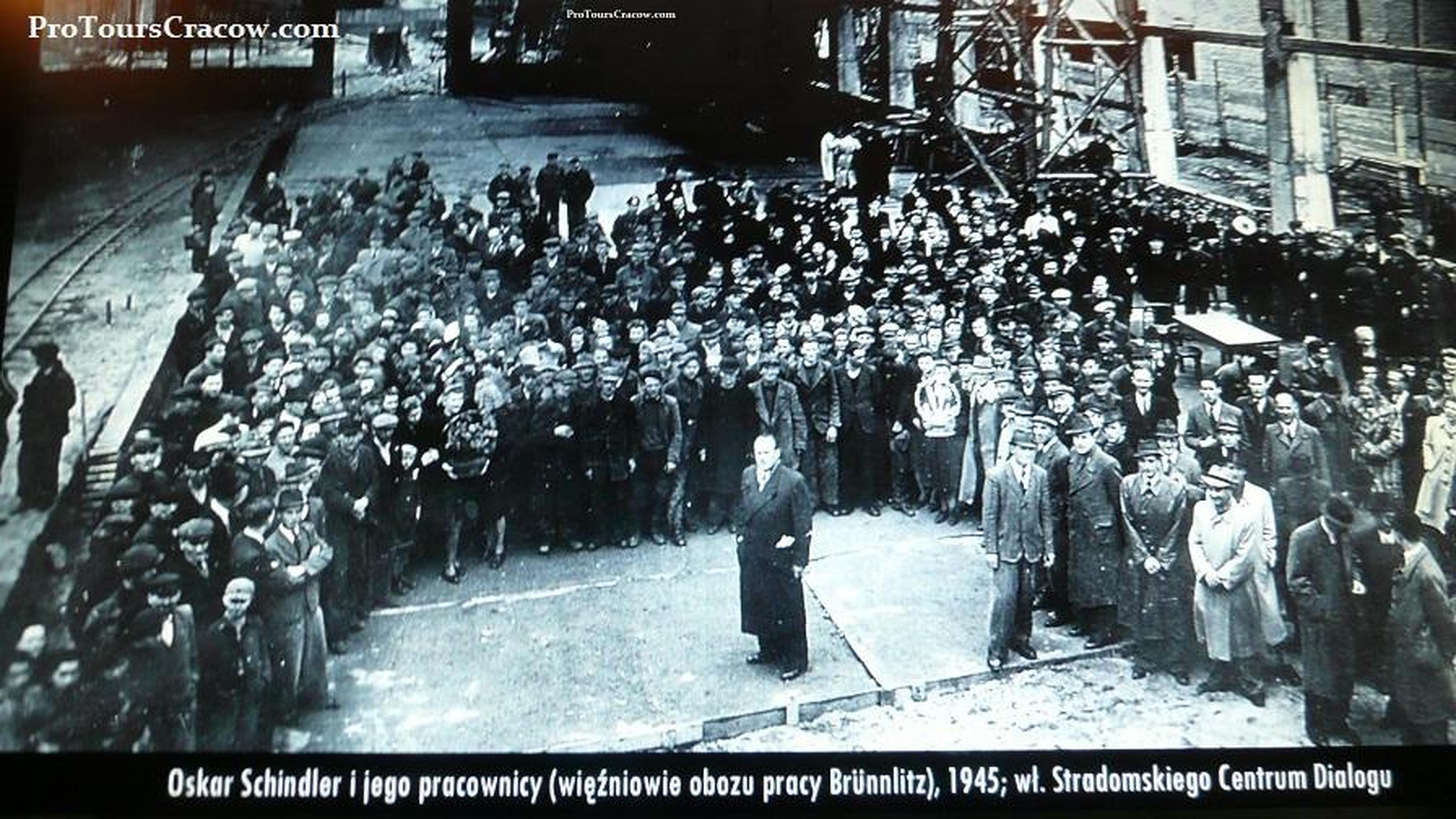

During the factory’s beginnings, Schindler hired only a few Jewish people who would help him manage the factory while he hired many non-Jewish poles to supply the labor. However, with the factory’s growth, particularly at its peak in 1944, the factory employed around 1,750 workers – 1,000 of whom were Jewish. As the years went by, Schindler saw with his own eyes the terrible crimes of the Nazis against the Jews. After having a change of heart with regard to the genocide, he began to use his factory as means of protecting his Jewish workers.

Schindler saved his workers by making undercover bargains, offering large bribes, and using connections in the Black Market to convince the Nazis to let him keep his Jewish staff. Schindler had initially hired Jewish people because they were cheaper by the Nazi wage than Polish laborers. Yet when the Jews were threatened with deportation and sentenced to death in Concentration Camps, Schindler began to shield his workers by paying the Nazis even higher sums.

Although he lost nearly all of his money by protecting his workers, he did his best to relocate them to safer areas and see that their lives were spared. He did undercover work for the Jewish Agency of Israel during the Second World War, reported the Nazi mistreatment of the Jews to people around the world, and used all of his connections to protect the Jews who worked for him.

The Jewish people he saved, who numbered about 1,200, are today nicknamed Schindlerjuden (German for “Schindler’s Jews”). After the war, these Jewish people honored their beloved hero by funding him monetarily and seeing that his life was honored by the State of Israel and Jewish people around the world. Schindler never saw much business success in the days following the war, but his life was celebrated by thousands worldwide.

In case you'd like to learn more about Oskar Schindler, please see the article about him in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum's Holocaust Encyclopedia. The link is: http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/article.php?ModuleId=10005787

During the factory’s beginnings, Schindler hired only a few Jewish people who would help him manage the factory while he hired many non-Jewish poles to supply the labor. However, with the factory’s growth, particularly at its peak in 1944, the factory employed around 1,750 workers – 1,000 of whom were Jewish. As the years went by, Schindler saw with his own eyes the terrible crimes of the Nazis against the Jews. After having a change of heart with regard to the genocide, he began to use his factory as means of protecting his Jewish workers.

Schindler saved his workers by making undercover bargains, offering large bribes, and using connections in the Black Market to convince the Nazis to let him keep his Jewish staff. Schindler had initially hired Jewish people because they were cheaper by the Nazi wage than Polish laborers. Yet when the Jews were threatened with deportation and sentenced to death in Concentration Camps, Schindler began to shield his workers by paying the Nazis even higher sums.

Although he lost nearly all of his money by protecting his workers, he did his best to relocate them to safer areas and see that their lives were spared. He did undercover work for the Jewish Agency of Israel during the Second World War, reported the Nazi mistreatment of the Jews to people around the world, and used all of his connections to protect the Jews who worked for him.

The Jewish people he saved, who numbered about 1,200, are today nicknamed Schindlerjuden (German for “Schindler’s Jews”). After the war, these Jewish people honored their beloved hero by funding him monetarily and seeing that his life was honored by the State of Israel and Jewish people around the world. Schindler never saw much business success in the days following the war, but his life was celebrated by thousands worldwide.

In case you'd like to learn more about Oskar Schindler, please see the article about him in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum's Holocaust Encyclopedia. The link is: http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/article.php?ModuleId=10005787

One of his workers would later tell the story of Oskar Schindler to Australian writer Thomas Keneally who wrote the novel about Schindler called Schindler’s Ark. The book was transformed into a screen play and the film Schindler’s List was filmed on location in Krakow, Poland, the production lead by director Steven Spielberg. The movie was nominated for many Academy Awards, winning seven of them including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay, and Best Original Score. It has been critically acclaimed is widely viewed as one of the best films ever made.

Between the success of the movie and the story of Schindler, Krakow is now visited by many Jewish people from around the world who want to learn about this incredible man and story of the 1,200 Jews he saved. The movie increased Krakow’s tourism rate immensely, producing a rise in its economy. There are signs describing the rich Jewish history of Krakow everywhere. When I was in Krakow, I had the opportunity to visit Schindler’s “Emalia” factory which is now a museum about Schindler and the history of the Nazi occupation in Krakow. It is a very packed museum, rich in history, artifacts, and writing. Unfortunately, I can’t say I learned a ton about Schindler by visiting the factory (there was no room dedicated solely to him) but I appreciated that the building still stands and is being used as a means to educate about the Holocaust and the destruction caused by the Nazis. Schindler is no longer alive today, but his memory remains a blessing.

Furthermore, we can thank Steven Spielberg, a courageous Jewish person himself, for documenting the life of Oskar Schindler and making a movie about him. Later, Spielberg created a foundation called the University of Southern California Shoah Foundation Institute for Visual History and Education which has to this day recorded over 53,000 Holocaust survivor and witness testimonies. Both he and Schindler are incredible heroes.

Between the success of the movie and the story of Schindler, Krakow is now visited by many Jewish people from around the world who want to learn about this incredible man and story of the 1,200 Jews he saved. The movie increased Krakow’s tourism rate immensely, producing a rise in its economy. There are signs describing the rich Jewish history of Krakow everywhere. When I was in Krakow, I had the opportunity to visit Schindler’s “Emalia” factory which is now a museum about Schindler and the history of the Nazi occupation in Krakow. It is a very packed museum, rich in history, artifacts, and writing. Unfortunately, I can’t say I learned a ton about Schindler by visiting the factory (there was no room dedicated solely to him) but I appreciated that the building still stands and is being used as a means to educate about the Holocaust and the destruction caused by the Nazis. Schindler is no longer alive today, but his memory remains a blessing.

Furthermore, we can thank Steven Spielberg, a courageous Jewish person himself, for documenting the life of Oskar Schindler and making a movie about him. Later, Spielberg created a foundation called the University of Southern California Shoah Foundation Institute for Visual History and Education which has to this day recorded over 53,000 Holocaust survivor and witness testimonies. Both he and Schindler are incredible heroes.

Now that you know about Oskar Schindler, let me tell you about the next woman whose story affected me just as deeply. I heard the story with my own ears at the Galicia Museum in Krakow. This woman’s story is incredible and I feel blessed that I could look into her eyes as she told it.

The woman that I met, Mirosława Gruszczyńska (née Przebindowska) was 10 years old when the Nazis took over her city of Krakow. By 1943, when she was 14 years old, she had been forced to watch as all of her Jewish classmates were removed from her school and neighborhood, shipped off to someplace where they would never come back. Mirosława lived in a small home with her mother Helena Przebindowska and her sixteen year old sister Urszula, struggling from a life of fear and discomfort under the Nazi rule.

In 1943, Mirosława and her family were offered the chance to do something that would change their world and young Mirosława’s life forever. In 1943, Mirosława’s aunt approached her mother Helena with the question of whether the family would be able to temporarily shelter a Jewish girl.

The woman that I met, Mirosława Gruszczyńska (née Przebindowska) was 10 years old when the Nazis took over her city of Krakow. By 1943, when she was 14 years old, she had been forced to watch as all of her Jewish classmates were removed from her school and neighborhood, shipped off to someplace where they would never come back. Mirosława lived in a small home with her mother Helena Przebindowska and her sixteen year old sister Urszula, struggling from a life of fear and discomfort under the Nazi rule.

In 1943, Mirosława and her family were offered the chance to do something that would change their world and young Mirosława’s life forever. In 1943, Mirosława’s aunt approached her mother Helena with the question of whether the family would be able to temporarily shelter a Jewish girl.

The girl’s name was Anna Allerhand but when she stayed with the Przebindowskas she went by ‘Marysia.’ Mirosława, her mother, and her sister all agreed that they would temporarily hide this girl. They did not know what to expect. They initially thought the hiding would last for just a few days. Little did they know there were other issues in store for them.

When Marysia arrived, she expressed her gratitude immediately that the Przebindowskas had agreed to help her. Mirosława recalls that the Marysia immediately ran up to her and embraced her, kissing her on both cheeks. Marysia exclaimed that they were going to become great friends. Mirosława didn’t see this coming – she had just planned on helping Marysia, but she had never thought that they would become friends.

In the first few days that she was at the Przebindowska home, Marysia came down with severe illness. She couldn’t even get out of bed, let alone leave the home. Unable to take Marysia to the doctor, the Przebindowskas did not know what to do. Eventually, Mirosława and her mother were able to get Marysia some medicine by faking that Mirosława was sick. Helena took Mirosława to the doctor’s office claiming that her daughter urgently needed medicine. Luckily the doctor prescribed Mirosława with the medicine that Marysia needed. With the medicine, Marysia was saved.

And that was just the first challenge the Przebindowskas faced.

After Marysia had returned to her normal health, the Przebindowska family had fallen in love with the Jewish girl. They couldn’t imagine her leaving, let alone sending her back out into the dangerous world where surely she’d be caught by the Nazis and sent to the camps. When asked if she ever thought twice about insisting for Marysia to stay, Mirosława said she never for a moment regretted her decision. She said that she had to do it because it was the right thing to do. Marysia was now a part of their family and they had to protect her. Much was at risk for the Przebindowska family. By hiding a Jew, if the family was caught, they would all be killed. The Nazis had no patience for people who hid Jews – if you hid them and you were caught, you would have the same dark fate.

When Marysia arrived, she expressed her gratitude immediately that the Przebindowskas had agreed to help her. Mirosława recalls that the Marysia immediately ran up to her and embraced her, kissing her on both cheeks. Marysia exclaimed that they were going to become great friends. Mirosława didn’t see this coming – she had just planned on helping Marysia, but she had never thought that they would become friends.

In the first few days that she was at the Przebindowska home, Marysia came down with severe illness. She couldn’t even get out of bed, let alone leave the home. Unable to take Marysia to the doctor, the Przebindowskas did not know what to do. Eventually, Mirosława and her mother were able to get Marysia some medicine by faking that Mirosława was sick. Helena took Mirosława to the doctor’s office claiming that her daughter urgently needed medicine. Luckily the doctor prescribed Mirosława with the medicine that Marysia needed. With the medicine, Marysia was saved.

And that was just the first challenge the Przebindowskas faced.

After Marysia had returned to her normal health, the Przebindowska family had fallen in love with the Jewish girl. They couldn’t imagine her leaving, let alone sending her back out into the dangerous world where surely she’d be caught by the Nazis and sent to the camps. When asked if she ever thought twice about insisting for Marysia to stay, Mirosława said she never for a moment regretted her decision. She said that she had to do it because it was the right thing to do. Marysia was now a part of their family and they had to protect her. Much was at risk for the Przebindowska family. By hiding a Jew, if the family was caught, they would all be killed. The Nazis had no patience for people who hid Jews – if you hid them and you were caught, you would have the same dark fate.

The Przebindowskas bravely took this risk to save Marysia. Another obstacle they faced was when another Polish family was forced to share their home with them. Wartime conditions often made this situation happen, where two families were forced to live together. The family that now shared the Przebindowka’s home was not accepting of Jewish people and would have certainly reported the Przebindowskas if they found out about Marysia’s being Jewish. The husband in the new family was an alcoholic and very abusive, often beating his wife and putting all who lived in the household in danger.

Life got a little easier for the Przebindowskas when they were able to entrust a local Priest, Father Faustyn, with Marysia’s identity. The Priest was a friend of the family agreed to keep the secret. He was able to forge Baptism papers for Marysia which in a way freed her. With a new proclaimed “Aryan” identity, Marysia could now safely walk around the home. In fact, now she could walk safely around Krakow without great fear of being arrested, although she had to be cognizant that some people might recognize her from her real identity.

From then on the family introduced their Jewish resident as Marysia Malinowska, a Catholic girl from Eastern Poland. There were a few events where her real identity was almost revealed, however, luckily, Marysia and the Przebindowskas could keep the secret and remain safe until the end of the war.

When the war ended in 1945 and the German troops had left, the question arose as to where Marysia would go. At that point Marysia was fifteen years old, way behind in school, and there were hardly any Jews left alive in Krakow. The Przebindowskas invited Marysia to stay with them – they would adopt her as a third daughter. Helena homeschooled Marysia so she could catch up in school – thanks to her, Marysia later ended up passing her exams perfectly.

In May 1945, Marysia’s father Leopold came back. Her father had served as a soldier in the Polish army and for a while was held at a German POW camp. Marysia’s brother Aleksander also came back. He was shipped from camp to camp and was eventually one of the 1,200 Jews fortunate enough to be put on Schindler’s list. He was held at Schindler’s Brunnlitz camp, where he was liberated. Lastly, after Marysia, her father, and her brother were reunited, they found her twin sister Róża who was saved by a nearby family of farmers. The only member of her immediate family who died was her mother – she was a lucky girl compared to many survivors who lost their entire family in the war.

Soon afterwards, Marysia and Róża left for Israel, where they were later joined by their father and their brother after he graduated from university in Poland. Many Jewish people who survived the war ended up moving to Palestine to help found the Jewish State.

Life got a little easier for the Przebindowskas when they were able to entrust a local Priest, Father Faustyn, with Marysia’s identity. The Priest was a friend of the family agreed to keep the secret. He was able to forge Baptism papers for Marysia which in a way freed her. With a new proclaimed “Aryan” identity, Marysia could now safely walk around the home. In fact, now she could walk safely around Krakow without great fear of being arrested, although she had to be cognizant that some people might recognize her from her real identity.

From then on the family introduced their Jewish resident as Marysia Malinowska, a Catholic girl from Eastern Poland. There were a few events where her real identity was almost revealed, however, luckily, Marysia and the Przebindowskas could keep the secret and remain safe until the end of the war.

When the war ended in 1945 and the German troops had left, the question arose as to where Marysia would go. At that point Marysia was fifteen years old, way behind in school, and there were hardly any Jews left alive in Krakow. The Przebindowskas invited Marysia to stay with them – they would adopt her as a third daughter. Helena homeschooled Marysia so she could catch up in school – thanks to her, Marysia later ended up passing her exams perfectly.

In May 1945, Marysia’s father Leopold came back. Her father had served as a soldier in the Polish army and for a while was held at a German POW camp. Marysia’s brother Aleksander also came back. He was shipped from camp to camp and was eventually one of the 1,200 Jews fortunate enough to be put on Schindler’s list. He was held at Schindler’s Brunnlitz camp, where he was liberated. Lastly, after Marysia, her father, and her brother were reunited, they found her twin sister Róża who was saved by a nearby family of farmers. The only member of her immediate family who died was her mother – she was a lucky girl compared to many survivors who lost their entire family in the war.

Soon afterwards, Marysia and Róża left for Israel, where they were later joined by their father and their brother after he graduated from university in Poland. Many Jewish people who survived the war ended up moving to Palestine to help found the Jewish State.

After several years of staying in touch, in 1968, Marysia and Mirosława lost contact because the communist powers who had taken over Poland didn’t allow mail from outside countries. It wasn’t until 1989 that the two could be in touch again, when the powers of communism fell. The two friends hadn’t spoken in more than twenty years.

Marysia took her family back to Krakow to visit Mirosława and her family. Mirosława described it as a very special and emotional visit – one that was very important to both of them. Later, in 1990, Mirosława went with her family to visit Marysia in Israel. On March 7, 1990, Mirosława, her mother Helena and her sister Urszula were recognized as the Righteous Among the Nations. Mirosława passed her medal and certificate around the room for everyone to touch and see. It was a very special moment to be able to hold this certificate, feeling the weight of all that it meant.

I couldn’t believe I was sitting in front of somebody who had done something so heroic. Several of the girls in my group just sat there stunned, so amazed and not even sure what to say. Do you say thank you? Is that even enough? Several of the girls had tears in their eyes.

We thanked Mirosława for her time and for sharing her story with us. She gladly smiled and said in her native Polish that she was happy to do it. It’s amazing to me how heroes can be so modest. To Mirosława she wasn’t doing something so outrageous or heroic – she was simply doing what she had to do. She couldn’t just watch the evil around her continue so she acted on her beliefs and ended up saving a life. She also made a dear friend whose descendents would later know that without Mirosława, none of them would be living.

I couldn’t believe I was sitting in front of somebody who had done something so heroic. Several of the girls in my group just sat there stunned, so amazed and not even sure what to say. Do you say thank you? Is that even enough? Several of the girls had tears in their eyes.

We thanked Mirosława for her time and for sharing her story with us. She gladly smiled and said in her native Polish that she was happy to do it. It’s amazing to me how heroes can be so modest. To Mirosława she wasn’t doing something so outrageous or heroic – she was simply doing what she had to do. She couldn’t just watch the evil around her continue so she acted on her beliefs and ended up saving a life. She also made a dear friend whose descendents would later know that without Mirosława, none of them would be living.

I am awed by people like Mirosława and Oskar Schindler. They give me faith in people and faith in humanity. They and righteous people like them are the reason I continue to believe in the good that can be found in the world. You see, with so much destruction and wrong doing on this earth now, we need models in order to remain hopeful. The key to choosing life, for them, was not to give up; rather, it was to be brave and to do what their heart told them was right. Remember, as it says in the Talmud, he who saves even one life, saves the entire world.

So that’s it for part two of my three part blog post. I hope you enjoyed it. In my next post, I’m going to tell you the story of the last part of my trip in Poland. I’m going to tell you about my discovery of incredible family history, the story of my last few days in Krakow and Warsaw, and lastly, just what it means to be a “Galitzyaner.” For that, you’ll have to wait and be surprised. As always thank you for reading.

Until next time,

Arielle

So that’s it for part two of my three part blog post. I hope you enjoyed it. In my next post, I’m going to tell you the story of the last part of my trip in Poland. I’m going to tell you about my discovery of incredible family history, the story of my last few days in Krakow and Warsaw, and lastly, just what it means to be a “Galitzyaner.” For that, you’ll have to wait and be surprised. As always thank you for reading.

Until next time,

Arielle

Works Cited:

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “Oskar Schindler.” Holocaust Encyclopedia. http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/article.php?ModuleId=100057873. Accessed on September 3, 2014.

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “Oskar Schindler.” Holocaust Encyclopedia. http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/article.php?ModuleId=100057873. Accessed on September 3, 2014.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed