Hi everyone! Thanks so much for tuning into the latest chapter of my journey studying Jewish life and culture in Eastern Europe. Saving the Shtetlach is back and I’m so glad you can join me. This post is going to be the final part of my three part Poland blog series. Coming up afterwards I have some surprises that I can’t wait to share with you.

Although my Poland trip occurred this past June, I can remember it as though it happened yesterday. It was such a meaningful trip for me. I’m not lying when I say it changed my life. It re-taught me how to think. I didn’t know if I’d ever be able to truly see Poland. When I say see, I mean, see it for anything besides its history of the Holocaust. I knew the country had a long history and the Jews lived there for a long time, but when I thought of Poland, the first thing that always came to my mind were the concentration camps. I could only see Auschwitz. I only saw death.

When I decided that I would spend some of my Woodrow Wilson scholarship funding to go on a trip to Poland, I knew I was making an important choice. I knew the choice would be life changing – I just hoped the choice was the right one.

Looking back on it now, let me assure you – going to Poland was one of the best decisions I’ve ever made. And I’m quite indecisive.

Before my trip to Poland, whenever I told people where I was going, the most common response was “Oh, well, I’d say have fun, but um, I don’t know.” One could say that that response was understandable. Most of the people I had spoken to, like myself, had never been to Poland. Most people hadn’t learned anything about Poland besides the history of the Shoah. Everyone assumed I’d have a sad trip because they thought that the Holocaust would be all that I would learn about. Truth was, I had no idea what I was going to learn.

When I hopped on the plane to Poland for a ten day journey there, I had no idea what to expect. I came in thinking I knew the history of Poland’s Jews, when in fact I had it written in my head completely wrong. I thought I understood the history of my ancestry, but how much can one truly understand when there is so much to be learned, so many stories to hear, so much to see. By the end of the trip, this history that I thought I knew had re-written me. I came in thinking I would only find death, when in fact, right in front of me, was 1000 years of life. It was right there waiting for me. I had just never looked to see it.

There were two experiences I had in Poland that really shaped my trip overall. These two experiences I think back on often and wonder how lucky I must have been to witness these happenings, how small a chance there was that all of this could have just happened and fallen into place. I’ve always believed in the Yiddish word bashert which means fate. Looking back I think I was really bashert-ed up on this trip. I couldn’t believe what I saw.

Although my Poland trip occurred this past June, I can remember it as though it happened yesterday. It was such a meaningful trip for me. I’m not lying when I say it changed my life. It re-taught me how to think. I didn’t know if I’d ever be able to truly see Poland. When I say see, I mean, see it for anything besides its history of the Holocaust. I knew the country had a long history and the Jews lived there for a long time, but when I thought of Poland, the first thing that always came to my mind were the concentration camps. I could only see Auschwitz. I only saw death.

When I decided that I would spend some of my Woodrow Wilson scholarship funding to go on a trip to Poland, I knew I was making an important choice. I knew the choice would be life changing – I just hoped the choice was the right one.

Looking back on it now, let me assure you – going to Poland was one of the best decisions I’ve ever made. And I’m quite indecisive.

Before my trip to Poland, whenever I told people where I was going, the most common response was “Oh, well, I’d say have fun, but um, I don’t know.” One could say that that response was understandable. Most of the people I had spoken to, like myself, had never been to Poland. Most people hadn’t learned anything about Poland besides the history of the Shoah. Everyone assumed I’d have a sad trip because they thought that the Holocaust would be all that I would learn about. Truth was, I had no idea what I was going to learn.

When I hopped on the plane to Poland for a ten day journey there, I had no idea what to expect. I came in thinking I knew the history of Poland’s Jews, when in fact I had it written in my head completely wrong. I thought I understood the history of my ancestry, but how much can one truly understand when there is so much to be learned, so many stories to hear, so much to see. By the end of the trip, this history that I thought I knew had re-written me. I came in thinking I would only find death, when in fact, right in front of me, was 1000 years of life. It was right there waiting for me. I had just never looked to see it.

There were two experiences I had in Poland that really shaped my trip overall. These two experiences I think back on often and wonder how lucky I must have been to witness these happenings, how small a chance there was that all of this could have just happened and fallen into place. I’ve always believed in the Yiddish word bashert which means fate. Looking back I think I was really bashert-ed up on this trip. I couldn’t believe what I saw.

While in Poland, I met someone that I had been searching for but never really knew I had. I met my great-great-grandmother Celia Bornstein and my life was changed permanently so for the better. Now you’re probably wondering, how on earth could I meet a great-great-grandmother? So okay, you’re right, I didn’t actually meet Celia when she was alive. She had passed away long before I was born. However, I did meet my great-great grandmother. How? Well it’s all thanks to the Jewish Historical Institute.

(Quick note: no people were actually brought back from the dead to write this blog post – you just have to pick up on my metaphors.)

When I arrived at the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw, Poland, I never expected to find anything substantial about my family. As a fourth generation American, I knew very little about my ancestors that once lived on these Eastern European distant lands. All I knew at the time of my trip was that I had a great-great-grandmother named Celia. She was the leading matriarch of my mother’s family – the woman who started the line of Bornsteins, to become Hurwitzes, to become Kadens – she started it all way back. Before my trip began, I asked my great-Aunt Marilyn to tell me everything that she knew about my great-great Grandmother. In her kind way, Marilyn told me that sadly she had very little information about Celia. She provided me the names of her immediate family, the name of their hometown Stryj, and Celia’s birth date on March 25, 1888. I wrote this information down in my brown journal and took it with me to the staff at the Jewish Historical Institute. What they did with that little bit of information – it blew me away.

(Quick note: no people were actually brought back from the dead to write this blog post – you just have to pick up on my metaphors.)

When I arrived at the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw, Poland, I never expected to find anything substantial about my family. As a fourth generation American, I knew very little about my ancestors that once lived on these Eastern European distant lands. All I knew at the time of my trip was that I had a great-great-grandmother named Celia. She was the leading matriarch of my mother’s family – the woman who started the line of Bornsteins, to become Hurwitzes, to become Kadens – she started it all way back. Before my trip began, I asked my great-Aunt Marilyn to tell me everything that she knew about my great-great Grandmother. In her kind way, Marilyn told me that sadly she had very little information about Celia. She provided me the names of her immediate family, the name of their hometown Stryj, and Celia’s birth date on March 25, 1888. I wrote this information down in my brown journal and took it with me to the staff at the Jewish Historical Institute. What they did with that little bit of information – it blew me away.

I was actually in touch with the JHI before I came to Poland because I had been interested in working there as a summer intern. The JHI had accepted my application to be an intern but sadly, I had to pull out of that job due to another job I had received at home. I was very disappointed that I couldn’t spend the summer working with the staff at the Jewish Historical Institute. Looking back now, I am so happy that I had the chance to stop in for a day when I was in Warsaw. When I arrived at the JHI, I was welcomed like a member of the family. As soon as I walked in, all of the staff hugged me and welcome me to Poland. They were so happy that I had made it to their country and they sat me down right away to help me research my ancestry. I sat down with a kind staff member named Anna and I told her everything I knew about my great-great-grandmother Celia. Together we looked her name up on their computer which was connected to various historical archives. From birth records to censuses, wedding documents to street maps, everything that has been found about Polish-Jewish Jewry can be researched at the Jewish Historical Institute. It is truly an amazing place and I never thought I’d find what I found there.

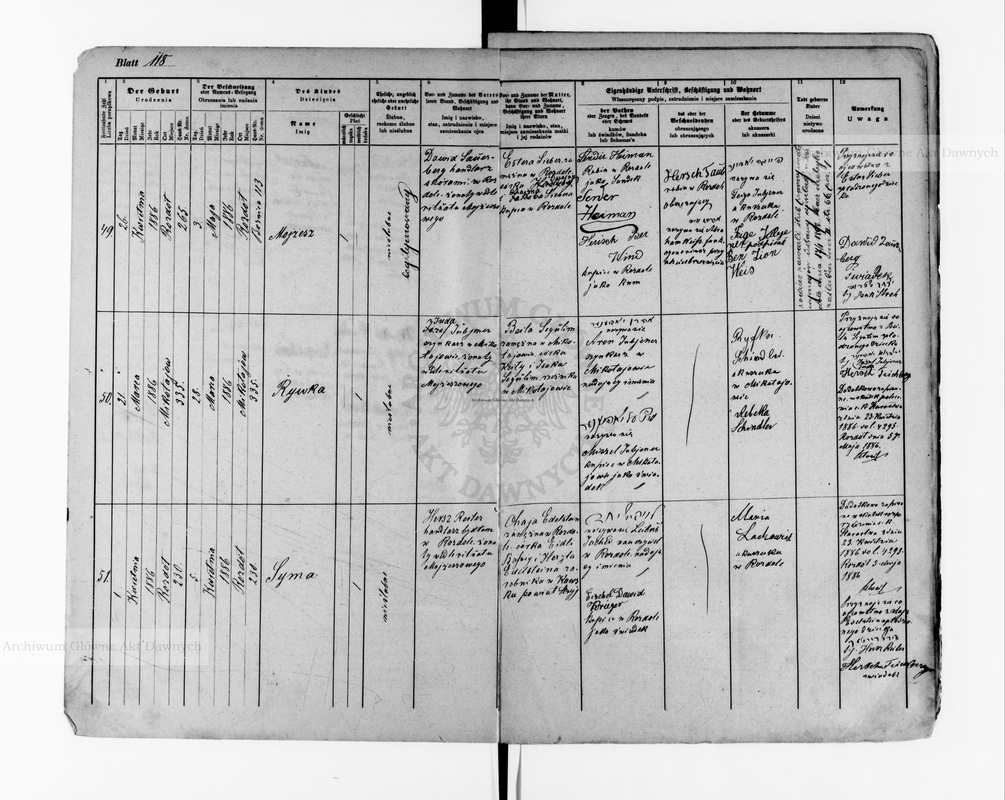

Within fifteen minutes of research, Anna’s work had completely reshaped everything I understood about my family’s ancestry. She found information so quickly that I couldn’t believe my eyes. I didn’t even know there were files that still existed regarding my family. A common misconception that most Jewish people have about their ancestry is that when the Holocaust happened and most of the Jews disappeared, so did all of the records. But it is not true. It is true that many records were destroyed – but not all of them. In fact, many records made it through the war and today they are organized and put in archives for people to go back to and use for research.

It turned out that the JHI could not only find information about Celia, but they also found out information about all of her siblings. They found birth records for everyone. They found files on Celia’s parents, her father’s job, her mother’s parents, etc. It was unbelievable. They even found Celia’s street address. I learned a lot of new things about Celia when I was at the Jewish Historical Institute – and here are a few of them.

Within fifteen minutes of research, Anna’s work had completely reshaped everything I understood about my family’s ancestry. She found information so quickly that I couldn’t believe my eyes. I didn’t even know there were files that still existed regarding my family. A common misconception that most Jewish people have about their ancestry is that when the Holocaust happened and most of the Jews disappeared, so did all of the records. But it is not true. It is true that many records were destroyed – but not all of them. In fact, many records made it through the war and today they are organized and put in archives for people to go back to and use for research.

It turned out that the JHI could not only find information about Celia, but they also found out information about all of her siblings. They found birth records for everyone. They found files on Celia’s parents, her father’s job, her mother’s parents, etc. It was unbelievable. They even found Celia’s street address. I learned a lot of new things about Celia when I was at the Jewish Historical Institute – and here are a few of them.

- Celia’s name originally wasn’t Celia – it was Syma – her name later became Celia when she arrived in the United States.

- Her last name was Reiter, not Ritter.

- She lived in Rozdół, Poland (a town very close to Stryj) – now part of Ukraine.

- She was born on April 1, 1886 in house number 230. She had her baby naming on April 5, 1886.

- Her father’s name was Hersz Reiter and he was a cattle trader.

- Her mother’s name was Chaja (Chaya) Edelstein.

- Her mother’s parents names were Basia and Herzl Edelstein. Herzl worked in Kawsko, Stryj county.

- Syma had many siblings, all in similar age to her.

As I sat there in the Jewish Historical Institute, looking at all the information they had pulled up about Syma, I could hardly control myself. I was beyond the point of amazed. I was touched. Something broke down inside of me that I couldn’t seem to put back together. It was like a wall deep in my heart had suddenly crumbled down. In the field of Holocaust and Eastern European Jewish studies, one often has to put up walls in their mind to prevent an overflow of emotion. In my life, I’ve needed to put up walls for myself because I’m such a sap. If I let myself, I’d be crying during every scene of a sentimental movie. I constantly have to tell myself to suppress my thoughts because the feeling is too much. It’s easier to harness my emotions than to let them go.

When I got back from the Jewish Historical Institute, I sat in my hotel room and cried. I couldn’t help it. The emotion was too much. I rarely let such emotion override me. But I didn’t know how to contain it. I always wondered why I didn’t cry when I was in Auschwitz. I was ashamed of myself. Yet here I was crying in my hotel room. I was crying, by myself, because I had seen some files on a computer.

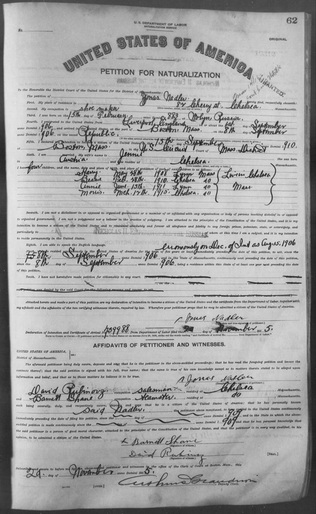

But, you see, I wasn’t crying tears of sadness. I was not sad at all. I was crying tears of joy – tears of gratitude. I could not believe that Syma existed. I mean – I knew she had existed. I know she lived her life because if she didn’t, I wouldn’t be here. But for some reason, seeing those files, seeing her birth certificate, her immigration records, and learning about her family confirmed her life in a way I never thought possible.

When I learned about Syma, for one of the first moments in my life, I knew exactly where I was. I knew exactly who I was and I knew exactly where I wanted to be. It’s hard to describe this feeling of happiness in words, but I’ll tell you that it was there. The feeling was so raw, so potent – it took over my whole being. It was the thought of seeing Syma’s life and the way she lived it that suddenly made my life all the more worthwhile. At that moment, I was so happy to be in Poland. I was so grateful. There was no other place I would have rather been.

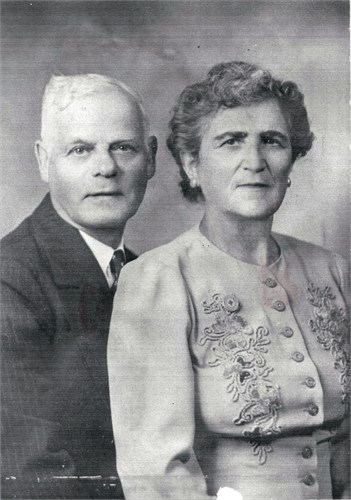

The following day, Anna from the JHI sent me an email with even more information about Syma. She sent me some documents and to my greater surprise, she sent me a picture. The image was not one of Syma, but rather it was a photograph of her older sister Scheindel sitting with her husband. Scheindel, who later went by Jennie was photographed here with her husband Jonas Nadler. Although they are much older in this picture, Scheindel and Jonas came together to the United States in 1907. At the time Scheindel was 22, and with her on the boat was her younger sister, Syma, who was 18. Their ship, called the S.S. Republic, sailed from Liverpool, England to Boston, Massachusetts. It was in Boston where both Scheindel and Syma began their lives as citizens of the United States.

When I got back from the Jewish Historical Institute, I sat in my hotel room and cried. I couldn’t help it. The emotion was too much. I rarely let such emotion override me. But I didn’t know how to contain it. I always wondered why I didn’t cry when I was in Auschwitz. I was ashamed of myself. Yet here I was crying in my hotel room. I was crying, by myself, because I had seen some files on a computer.

But, you see, I wasn’t crying tears of sadness. I was not sad at all. I was crying tears of joy – tears of gratitude. I could not believe that Syma existed. I mean – I knew she had existed. I know she lived her life because if she didn’t, I wouldn’t be here. But for some reason, seeing those files, seeing her birth certificate, her immigration records, and learning about her family confirmed her life in a way I never thought possible.

When I learned about Syma, for one of the first moments in my life, I knew exactly where I was. I knew exactly who I was and I knew exactly where I wanted to be. It’s hard to describe this feeling of happiness in words, but I’ll tell you that it was there. The feeling was so raw, so potent – it took over my whole being. It was the thought of seeing Syma’s life and the way she lived it that suddenly made my life all the more worthwhile. At that moment, I was so happy to be in Poland. I was so grateful. There was no other place I would have rather been.

The following day, Anna from the JHI sent me an email with even more information about Syma. She sent me some documents and to my greater surprise, she sent me a picture. The image was not one of Syma, but rather it was a photograph of her older sister Scheindel sitting with her husband. Scheindel, who later went by Jennie was photographed here with her husband Jonas Nadler. Although they are much older in this picture, Scheindel and Jonas came together to the United States in 1907. At the time Scheindel was 22, and with her on the boat was her younger sister, Syma, who was 18. Their ship, called the S.S. Republic, sailed from Liverpool, England to Boston, Massachusetts. It was in Boston where both Scheindel and Syma began their lives as citizens of the United States.

Both sisters settled in the neighborhood of Chelsea where they would each raise their families. Syma’s daughter would become my great-grandmother Bessie. Bessie, who also lived her life in Chelsea, would have a son who would become my grandfather Harvey. The family never left Chelsea until Harvey went to medical school and became a doctor in New York. There my grandpa Harvey and my grandmother Sara raised my Mom, Monica. And well, you know the rest – many years later my Mom met my Dad, and a few years after that came me.

I find learning about my ancestry absolutely thrilling. It’s become a passion of mine and I love exploring and learning new facts. Visiting the Jewish Historical Institute was like discovering a treasure trove that I never knew existed. It was completely mind blowing to see how much information one could find about their genealogy, even when beginning with very few facts. I am forever grateful to the JHI for their help and support. I walked away from the experience touched and genuinely inspired.

I find learning about my ancestry absolutely thrilling. It’s become a passion of mine and I love exploring and learning new facts. Visiting the Jewish Historical Institute was like discovering a treasure trove that I never knew existed. It was completely mind blowing to see how much information one could find about their genealogy, even when beginning with very few facts. I am forever grateful to the JHI for their help and support. I walked away from the experience touched and genuinely inspired.

The second experience I had in Poland that played a large part in shaping my trip was the night I spent having Shabbat dinner at the Jewish Community Center in Krakow. I had mentioned this dinner in Part I of my Poland series, but it touched me so much I thought I’d bring it up again. It’s funny how I can still remember that night so well.

When we first arrived at the Jewish Community Center in Krakow, we sat down with Jonathan Ornstein, the director of the JCC. He, along with the rest of the staff at the JCC was very kind to us. He explained to us why he chose to help run this organization in Krakow. He explained to us why the work they were doing was so important.

Before World War II, Krakow was a major center for Jewish life in Eastern Europe. The neighborhood of Kazimierz, which historically was known as the Jewish Quarter, was once the home to thousands of Jews. Jewish life thrived in Krakow before the war. From artists to business men, writers to doctors, Jews of all makes made their lives in Krakow. When the Second World War came around, everything changed. A Jewish ghetto was set, walls were put up, and most occupants in the run-down ghetto were later sent to Concentration Camps. Like many other European cities, out of the thousands of Jews that were shipped out of Krakow, after the war, hardly any Jews returned.

After the war, Krakow was not the same city. Without its vibrant Jewish population, the city lost the diversity that it had thrived on for nearly 1,000 years. As the Nazi banners were taken down, the city could not return back to normalcy. Krakow and Poland as a country were hit with back to back traumas. Just after the inexplicable trauma of the Second World War, in came communism – a regime which was by few means easier to live under. Surely, the Nazis were gone – but freedom – that was not present. When communism arose in Poland after the war, life could not be free. Individuality in all of its ways was suppressed, particularly, the ability to express religious belief. Thus for many Jews that remained in Krakow after the war, expressing their Jewish identity was viewed as a radical and dangerous idea. Some Jews lost their faith after the war. Some were okay with putting away their religious past and focusing on a secular future. But for some survivors, this inability to express their religion was not okay Some prayed that a time would come when they could once again express their religious identity. They prayed for an age where they could finally be proud to be who they were.

Twenty five years ago that day came when the Solidarity movement in Poland arose and pushed communism out. Polish society has changed drastically since that moment and this change can be seen particularly well when looking at the country’s relationship with Jewish life. In twenty five years, Jewish life in Poland has risen out of the ashes. It has been able to show its true colors.

When we first arrived at the Jewish Community Center in Krakow, we sat down with Jonathan Ornstein, the director of the JCC. He, along with the rest of the staff at the JCC was very kind to us. He explained to us why he chose to help run this organization in Krakow. He explained to us why the work they were doing was so important.

Before World War II, Krakow was a major center for Jewish life in Eastern Europe. The neighborhood of Kazimierz, which historically was known as the Jewish Quarter, was once the home to thousands of Jews. Jewish life thrived in Krakow before the war. From artists to business men, writers to doctors, Jews of all makes made their lives in Krakow. When the Second World War came around, everything changed. A Jewish ghetto was set, walls were put up, and most occupants in the run-down ghetto were later sent to Concentration Camps. Like many other European cities, out of the thousands of Jews that were shipped out of Krakow, after the war, hardly any Jews returned.

After the war, Krakow was not the same city. Without its vibrant Jewish population, the city lost the diversity that it had thrived on for nearly 1,000 years. As the Nazi banners were taken down, the city could not return back to normalcy. Krakow and Poland as a country were hit with back to back traumas. Just after the inexplicable trauma of the Second World War, in came communism – a regime which was by few means easier to live under. Surely, the Nazis were gone – but freedom – that was not present. When communism arose in Poland after the war, life could not be free. Individuality in all of its ways was suppressed, particularly, the ability to express religious belief. Thus for many Jews that remained in Krakow after the war, expressing their Jewish identity was viewed as a radical and dangerous idea. Some Jews lost their faith after the war. Some were okay with putting away their religious past and focusing on a secular future. But for some survivors, this inability to express their religion was not okay Some prayed that a time would come when they could once again express their religious identity. They prayed for an age where they could finally be proud to be who they were.

Twenty five years ago that day came when the Solidarity movement in Poland arose and pushed communism out. Polish society has changed drastically since that moment and this change can be seen particularly well when looking at the country’s relationship with Jewish life. In twenty five years, Jewish life in Poland has risen out of the ashes. It has been able to show its true colors.

Today, the common misconception is that there are no Jews left in Poland. People cannot see why a Jew would want to live in a country that many years ago turned its back on its own people. Issues of forgiveness, trust, grudges, and fear all shape the international Jewish perspective of Poland. After the tragedy of the Second World War, many Jews feel instinctively that Poland would be the worst place to grow a Jewish population. But the thing is - despite all of these negative feels – Jews still live in Poland. To many Jews, Poland is still home. To my surprise, I learned that there is a whole Jewish population still living in Poland. This population is now – despite the odds – growing and thriving.

The fall of communism changed everything. When communism ended, Jewish grandparents could now tell their children and grandchildren that they were Jewish. Religion could now be expressed. This opened a whole world of opportunities for the re-growth of Poland’s Jewish community. Synagogues could open up. Jewish schools could be run. Within the past 25 years, there has been a whole new generation of teenagers who have been just discovering the truth regarding their Jewish identities. It has been a recent phenomenon but it is very prevalent in Polish society. It is now very common in Poland for young people to research their roots. Youths want to know the history of their family’s past. I’ve heard from many that when one finds out that he or she has Jewish roots, it is particularly exciting. It is estimated that there are over 25,000 Polish young people out there who have Jewish roots and may not know it yet.

The stories of these young people who are finding out they are amazing. Each story is so different yet so emotional. When I was sitting at the JCC in Krakow that Shabbat evening, I sat next to a young man. I won’t disclose his name so for the sake of this post, I’ll refer to him as K.

I first met K at the JCC in Krakow when we both attended Shabbat services. The service was beautiful. My group’s leader, Rabbi Josh, lead our Friday night service with his guitar. We were all sitting in a circle on the top floor of the JCC in a room which normally houses their preschool.

In the seat to my left sat an elderly woman. She eagerly sang the prayers and you could see the spirit in her eyes. She had dark brown hair and a face that looked wise as it did strong. I later learned that this woman’s name was Zosia and she was a Holocaust survivor. She had grown up in Krakow and after the war had decided to stay there.

The young man sitting to her left was also singing. He stared down at his book and sang the prayers, although I could tell by the way he sang that he had the songs memorized. I didn’t know what his name was at the time but I thought I recognized his t-shirt. It was the same color t-shirt that my tour guide at Auschwitz was wearing – royal blue.

When services ended and we all sat down for dinner, I happened to sit across the table from the young man. He was quiet at first and spoke to his Polish friends sitting nearby. But as dinner went on and me and my American friends were acting quite silly (we had just spent the day in Auschwitz, we needed to lighten the mood), he decided to speak to us.

He introduced himself to us and we began to chat. Over the course of the conversation I learned a lot about K – he had a really interesting life, some of which, I’ll share with you.

The first thing you ought to know about K is that he was not always Jewish. Or better wording: for most his life he did not know that he was Jewish. When he was 18 years old, K found out from someone in his family that he had Jewish roots. He researched it more and found out that indeed, he was Jewish. This discovery totally changed his life.

His parents had grown up having to adhere to communist ideologies. K, growing up in Poland, had never had the opportunity to have any real exposure to Judaism, let alone religion. After he found out he had Jewish roots, K decided that he would totally change his life. For one, he got a circumcision. He started going to synagogue and decided to go to Jagiellonian University in Krakow and study Judaic and Near Eastern studies. He joined a Zionist youth movement and travelled to Israel. Today, he still lives in Krakow and is a tour guide at Auschwitz. I asked him how he does this job and he said it was hard, but someone had to do it. He takes breaks – he does a few days of tour guiding, and then he’ll take a week off. I think I’d probably do that if I were in his shoes.

K goes to the JCC in Krakow a lot. He understands how important and valuable the Jewish community in Krakow is. He was wearing a ring on his finger and I asked him what it said. He looked at it and smiled. He said it says the Shema.

And that’s when it hit me. K was just like me. Yes, he was older, a guy, living in Krakow, and had a totally different life than me. But yet we were the same. He was Jewish. I was Jewish. He had an interest in his identity. I… well, I was still finding mine. But yet with him I felt this instant connection. We talked the whole dinner and shared our stories.

He introduced me to his Polish friends sitting nearby. Many of them also found out as young adults that they were Jewish. One girl at the table said that her entire life she wished she was Jewish. She felt something instinctively in her heart telling her that she had Jewish roots, although for most of her life she had no information to back it up. It was only when she and her grandfather were sitting in a room together and some piano piece came on the radio that she learned the truth of her identity. When the piece began playing on the radio, her grandfather started to cry. She didn’t understand why this piece so special to her grandfather. It was then that he told her. The piece must have brought back some memory for him that reminded him of his Jewish identity and the secret he was holding within him.

This girl I met was so happy to learn that she had Jewish roots. She immediately went to the Rabbi and she became a member of the Polish Jewish community. Since then, she has, like K, made herself a constant presence at the JCC Krakow. They both decided that the life they wanted to live was a Jewish one.

It’s amazing how many stories there are like this one. It is a phenomenon sweeping across a generation. I cannot describe the excitement I felt when listening to these stories. They were so powerful. They reminded me of my own pride in being a Jewish person. They reminded of how lucky I was that my parents and my grandparents were always free to express themselves and their religious identity. I felt lucky that I could. I learned that there is no direct path to becoming a religious person– every one finds it in their own way if they want it. For some people, faith is there all along. For others, like myself, sometimes we have to go looking for it. And sometimes, if we are lucky; when we are least expecting it; when we think everything has gone astray – sometimes faith finds us.

It was a beautiful night spent eating and singing at the JCC Krakow. They made me feel like I was at home. Poland made me feel this too. Whether I was on the streets of Warsaw or Krakow, driving through the countryside or walking through the small shtetlach in between, I could feel history’s breath blowing in the wind. Whether I was standing in the JCCs of Krakow or Warsaw, walking through Poland’s several active synagogues, visiting Poland’s Jewish museums, or meeting the children of Warsaw’s Jewish day school, I began to feel the heart beat of not just the Jewish history in Poland, but also the Jewish life there that still exists. Mr. Ornstein said something interesting to us on this matter. In regards to Jewish life in Poland he said, “We are not here because of Auschwitz. We are here despite it.”

And that was when it all became clear to me. Throughout history, the resilience of the Jewish people has been shown in many different ways. From the rebuilding the temple in Jerusalem, to the Jews continuing their way to the Promised Land even without Moses – the truth is that the Jews have shown their strength and resilience at many different points in time. The spirit of the Jewish people relies in our constant faith. It relies in our ability to get back up. After the Holocaust, what may be considered history’s biggest blow to the Jewish people – or really to anyone in general – nobody thought that the Jewish people could come back in the way that they did. Yet look at the present day. Now there is a state of Israel. Now Jews are living almost everywhere in the world. Now we are free. We are free to be ourselves and we are free to prosper. I am so grateful for this freedom and it fills my heart to see the Jewish people of Poland embracing it as well. Their ability to get back up after the Second World War; their ability to overcome communism and rebuild a Jewish community that was so severely damaged after all this time is awe inspiring. I am forever grateful that I got to be in Poland to witness it – even if it was for just ten days.

The fall of communism changed everything. When communism ended, Jewish grandparents could now tell their children and grandchildren that they were Jewish. Religion could now be expressed. This opened a whole world of opportunities for the re-growth of Poland’s Jewish community. Synagogues could open up. Jewish schools could be run. Within the past 25 years, there has been a whole new generation of teenagers who have been just discovering the truth regarding their Jewish identities. It has been a recent phenomenon but it is very prevalent in Polish society. It is now very common in Poland for young people to research their roots. Youths want to know the history of their family’s past. I’ve heard from many that when one finds out that he or she has Jewish roots, it is particularly exciting. It is estimated that there are over 25,000 Polish young people out there who have Jewish roots and may not know it yet.

The stories of these young people who are finding out they are amazing. Each story is so different yet so emotional. When I was sitting at the JCC in Krakow that Shabbat evening, I sat next to a young man. I won’t disclose his name so for the sake of this post, I’ll refer to him as K.

I first met K at the JCC in Krakow when we both attended Shabbat services. The service was beautiful. My group’s leader, Rabbi Josh, lead our Friday night service with his guitar. We were all sitting in a circle on the top floor of the JCC in a room which normally houses their preschool.

In the seat to my left sat an elderly woman. She eagerly sang the prayers and you could see the spirit in her eyes. She had dark brown hair and a face that looked wise as it did strong. I later learned that this woman’s name was Zosia and she was a Holocaust survivor. She had grown up in Krakow and after the war had decided to stay there.

The young man sitting to her left was also singing. He stared down at his book and sang the prayers, although I could tell by the way he sang that he had the songs memorized. I didn’t know what his name was at the time but I thought I recognized his t-shirt. It was the same color t-shirt that my tour guide at Auschwitz was wearing – royal blue.

When services ended and we all sat down for dinner, I happened to sit across the table from the young man. He was quiet at first and spoke to his Polish friends sitting nearby. But as dinner went on and me and my American friends were acting quite silly (we had just spent the day in Auschwitz, we needed to lighten the mood), he decided to speak to us.

He introduced himself to us and we began to chat. Over the course of the conversation I learned a lot about K – he had a really interesting life, some of which, I’ll share with you.

The first thing you ought to know about K is that he was not always Jewish. Or better wording: for most his life he did not know that he was Jewish. When he was 18 years old, K found out from someone in his family that he had Jewish roots. He researched it more and found out that indeed, he was Jewish. This discovery totally changed his life.

His parents had grown up having to adhere to communist ideologies. K, growing up in Poland, had never had the opportunity to have any real exposure to Judaism, let alone religion. After he found out he had Jewish roots, K decided that he would totally change his life. For one, he got a circumcision. He started going to synagogue and decided to go to Jagiellonian University in Krakow and study Judaic and Near Eastern studies. He joined a Zionist youth movement and travelled to Israel. Today, he still lives in Krakow and is a tour guide at Auschwitz. I asked him how he does this job and he said it was hard, but someone had to do it. He takes breaks – he does a few days of tour guiding, and then he’ll take a week off. I think I’d probably do that if I were in his shoes.

K goes to the JCC in Krakow a lot. He understands how important and valuable the Jewish community in Krakow is. He was wearing a ring on his finger and I asked him what it said. He looked at it and smiled. He said it says the Shema.

And that’s when it hit me. K was just like me. Yes, he was older, a guy, living in Krakow, and had a totally different life than me. But yet we were the same. He was Jewish. I was Jewish. He had an interest in his identity. I… well, I was still finding mine. But yet with him I felt this instant connection. We talked the whole dinner and shared our stories.

He introduced me to his Polish friends sitting nearby. Many of them also found out as young adults that they were Jewish. One girl at the table said that her entire life she wished she was Jewish. She felt something instinctively in her heart telling her that she had Jewish roots, although for most of her life she had no information to back it up. It was only when she and her grandfather were sitting in a room together and some piano piece came on the radio that she learned the truth of her identity. When the piece began playing on the radio, her grandfather started to cry. She didn’t understand why this piece so special to her grandfather. It was then that he told her. The piece must have brought back some memory for him that reminded him of his Jewish identity and the secret he was holding within him.

This girl I met was so happy to learn that she had Jewish roots. She immediately went to the Rabbi and she became a member of the Polish Jewish community. Since then, she has, like K, made herself a constant presence at the JCC Krakow. They both decided that the life they wanted to live was a Jewish one.

It’s amazing how many stories there are like this one. It is a phenomenon sweeping across a generation. I cannot describe the excitement I felt when listening to these stories. They were so powerful. They reminded me of my own pride in being a Jewish person. They reminded of how lucky I was that my parents and my grandparents were always free to express themselves and their religious identity. I felt lucky that I could. I learned that there is no direct path to becoming a religious person– every one finds it in their own way if they want it. For some people, faith is there all along. For others, like myself, sometimes we have to go looking for it. And sometimes, if we are lucky; when we are least expecting it; when we think everything has gone astray – sometimes faith finds us.

It was a beautiful night spent eating and singing at the JCC Krakow. They made me feel like I was at home. Poland made me feel this too. Whether I was on the streets of Warsaw or Krakow, driving through the countryside or walking through the small shtetlach in between, I could feel history’s breath blowing in the wind. Whether I was standing in the JCCs of Krakow or Warsaw, walking through Poland’s several active synagogues, visiting Poland’s Jewish museums, or meeting the children of Warsaw’s Jewish day school, I began to feel the heart beat of not just the Jewish history in Poland, but also the Jewish life there that still exists. Mr. Ornstein said something interesting to us on this matter. In regards to Jewish life in Poland he said, “We are not here because of Auschwitz. We are here despite it.”

And that was when it all became clear to me. Throughout history, the resilience of the Jewish people has been shown in many different ways. From the rebuilding the temple in Jerusalem, to the Jews continuing their way to the Promised Land even without Moses – the truth is that the Jews have shown their strength and resilience at many different points in time. The spirit of the Jewish people relies in our constant faith. It relies in our ability to get back up. After the Holocaust, what may be considered history’s biggest blow to the Jewish people – or really to anyone in general – nobody thought that the Jewish people could come back in the way that they did. Yet look at the present day. Now there is a state of Israel. Now Jews are living almost everywhere in the world. Now we are free. We are free to be ourselves and we are free to prosper. I am so grateful for this freedom and it fills my heart to see the Jewish people of Poland embracing it as well. Their ability to get back up after the Second World War; their ability to overcome communism and rebuild a Jewish community that was so severely damaged after all this time is awe inspiring. I am forever grateful that I got to be in Poland to witness it – even if it was for just ten days.

On my trip, I was told about an old folktale that was passed down by Jews from generation to generation. It says that when the Jewish people first arrived in Poland – more than 1,000 years ago – as they walked through the tall pine forests surrounding them they heard a divine voice speaking from the trees. Its voice blew into their hearts like the feeling of wind. They could feel God’s presence pounding in their hearts. The voice said, “Po-lin… Po-lin,” which means in Hebrew, “Here you shall dwell.” It is said that Poland was once a haven for the Jews; it was a place they could call home. While many feel that the Holocaust and the creation of the State of Israel would negate this idea, for some reason, it still rings true to me. Despite the Holocaust, the Jewish people made their lives here in Poland for more than 1,000 years. They knew the land and they knew the people; they knew the fields, and they knew the waters. From the forests, they built homes and synagogues. Out of themselves, they built shtetls – communities.

This folktale makes me proud to see that the Jewish community is still alive and thriving in Poland. I am a believer that Jewish people should be able to make their home anywhere in the world. To me, home is where the heart is.

Looking back, travelling to Poland this summer was one of the greatest experiences of my life. In hearing the voices and stories of so many others – I felt like I could finally hear my own voice. In finding the traces of my great-great-grandmother’s life, I felt that I could take one step further in watering the roots of my own.

I know that one day the roots I'm growing now within myself will create branches. This trip showed me that it is okay if not everything in my life is well-planned. Sometimes, life just happens. Sometimes, when you lease expect it, the answers are just there waiting for you. Sometimes, you need to find out who you are first, before you can discover who you are supposed to be.

Thank you all so much for tuning in again to Saving the Shtetlach. In my next post I will take you somewhere you probably didn't expect. Why won’t you expect it – well, because frankly I didn't expect it myself. As a preview, I’ll tell you that I’m starting to think that perhaps the whole world is a Shtetlach – perhaps we are all one big community. So if that is the case, why not explore it a bit? It’s been a pleasure writing and thanks again for reading.

Until next time,

Arielle

This folktale makes me proud to see that the Jewish community is still alive and thriving in Poland. I am a believer that Jewish people should be able to make their home anywhere in the world. To me, home is where the heart is.

Looking back, travelling to Poland this summer was one of the greatest experiences of my life. In hearing the voices and stories of so many others – I felt like I could finally hear my own voice. In finding the traces of my great-great-grandmother’s life, I felt that I could take one step further in watering the roots of my own.

I know that one day the roots I'm growing now within myself will create branches. This trip showed me that it is okay if not everything in my life is well-planned. Sometimes, life just happens. Sometimes, when you lease expect it, the answers are just there waiting for you. Sometimes, you need to find out who you are first, before you can discover who you are supposed to be.

Thank you all so much for tuning in again to Saving the Shtetlach. In my next post I will take you somewhere you probably didn't expect. Why won’t you expect it – well, because frankly I didn't expect it myself. As a preview, I’ll tell you that I’m starting to think that perhaps the whole world is a Shtetlach – perhaps we are all one big community. So if that is the case, why not explore it a bit? It’s been a pleasure writing and thanks again for reading.

Until next time,

Arielle

This is a photograph of a photograph. The picture is of a lion painting in a former synagogue in Poland. During the Holocaust, the synagogue was nearly destroyed and Nazis defaced this lion. Years later, the lion was found and its face was restored. To me, this act of repainting the lion's face symbolizes the return of Poland's Jews - that no matter what - the Jewish people, like the face of a lion, would always be there. (courtesty: Galicia Museum in Krakow)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed